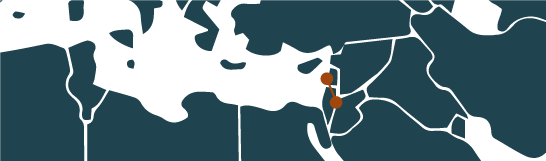

The longest street in the Middle East runs through the heart of Tehran. Extending from north to south, from the railway station up to Tajrish Square, it bisects the city into its eastern and western halves. The street's duality - desert and mountains connected over nearly twenty kilometres - is not only topographical. It is also social: the street's gradient climbs 700 metres from the poor south to the affluent north.

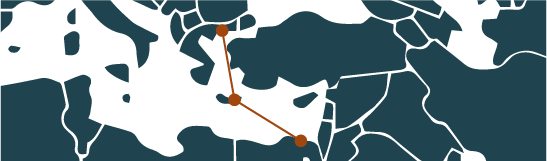

The tree-lined road was built by the order of Reza Shah (the founder of the Pahlavi dynasty) to connect the lowland city centre at the bottom of Tehran's plain to Reza Shah's royal summerhouse at the foot of the Alborz Mountains. This street, nearly a century old, and its 60,000 sycamore trees - which are decreasing in number every day - have recently been added to the national heritage list.

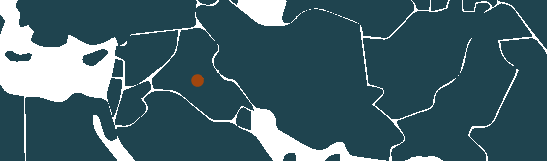

Before the Islamic Revolution of 1979, the street was named Pahlavi, in honour of the monarchy. Following the Revolution, the street was renamed Mossadegh after the former Iranian prime minister - a national hero and one of the main figures behind the nationalisation of Iran's oil, whose government was overthrown by a CIA-supported military coup in August of 1953.

It wasn't long before a strong objection to the name Mossadegh was voiced at a Friday prayer session, and was followed up on in parliament. Pressure by influential political figures like Ayatollah Shajuni, who were seeking to strike a balance between Islamists and nationalists, led to the street being divided into two nine kilometre halves - one named after Mossadegh and the other after his rival, the prominent Shia cleric Ayatollah Kashani [1]. Some religious nationalists, however, also opposed this renaming. The final decision was to choose a superior name, a name that stood above all objections: Valiasr, or "Heir to Eras", a reference to the Shi'ite messiah, the 12th Imam.

Different names have coexisted simultaneously. New signs have replaced old ones, but the street's official names never succeeded in conquering the entirety of Iran's population. One can take a political stance simply by referring to the street as Pahlavi instead of Valiasr.

This garden route is the backbone of the Iranian capital, and all main roads lead to it, one way or another. This territorial accessibility has also enabled sociopolitical mobility. During the disputed 2009 election and the uprisings that followed it, Valiasr became one of the largest gathering points of the opposition Green Movement.

It became a geopolitical strand, at least insofar as people began attributing political value to the street. When the municipality of Tehran transformed it into a one-way street, many interpreted the decision as an attempt to paralyse protests, rather than a solution to traffic congestion, as it claimed to be.

In Tehran, what marks space as public is a certain inescapability, rather than a social function or qualities like openness and accessibility - characteristics through which public space is conventionally defined. Tehran is not a generous city: public squares are islands of traffic rather than stages for public life. Strolling and conversing in public, as well as negotiating and appropriating shared space, are challenges in a city with immense, snaking highways, and streets choked by four million vehicles.

The characteristics of the built environment can alter, favour or hinder the spontaneous appropriation of space by people. In the case of Tehran, unwelcoming physical space and restrictions on appearance and behaviour imposed by state power have discouraged public life. Only veiled, censured and reduced versions of lifestyles, personalities and ideologies are permitted.

In this context, a street like Valiasr is rather exceptional in its configuration. Stretching from north to south, it mirrors the socio-spatial structure of the city and represents a condensed version of it. If you've walked along the whole road, you can claim to have seen Tehran in its entirety. In a 2010 survey, 90 per cent of Tehranis polled chose Valiasr as their favourite street in the city [2]. With its broad sidewalks, old sycamores and wide canals, Valiasr attracts a diversity of strollers, commuters, window shoppers and families. It provides opportunities for encounters despite constraints and controls.

Just as a society is unable to realise what is not dreamt by its members, it cannot be prevented from actualising at least some of their dreams [3]. The Tehran of today is a car-dominated city where the pedestrian is despised and facilitating any kind of gathering or assembly is a challenge. Valiasr, on the other hand, has been effectively appropriated by people both in their everyday life and in their moments of collective action. This has been accomplished, interestingly, despite the overwhelming presence of cars and the strict civic controls of the state. A shared social imaginary "makes possible common practices and a widely shared sense of legitimacy." [5]

Given Valiasr's appropriate length and its pivotal position, both in the geography of the city and the imaginary of its citizens, the idea of a Tehran half-marathon is appealing.

A marathon is a participatory process - not only in how it is performed, but also in its preparation. Thinking of a marathon in Tehran presupposes a different city, where well-being is a priority, where pedestrians can meet, breathe and run, where collective action is imaginable and possible, where men and women can blend into a single acting body and where difference is a source of richness rather than segregation.

To think of Tehran's half-marathon is to think of civil society demanding its democratic rights and its desire for a more liveable city, running from one end of the city to the other, to convey the victory of the pedestrian over cars - and of the people over power.