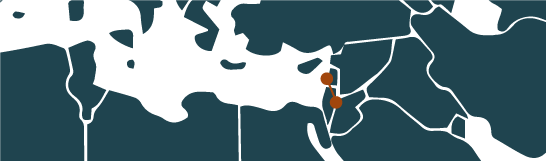

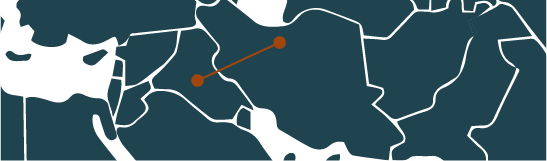

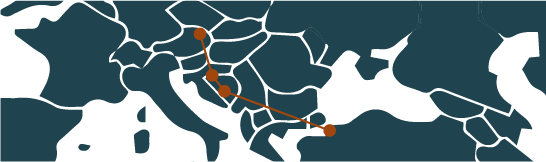

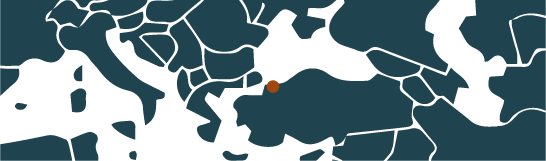

The impact that the Nairn Transport Company had on the region is undeniable: they paved the way for motor transport across the Syrian Desert and the Jordan Valley. Though the mail they transported was mostly diplomatic and served the foreign legions stationed in the Middle East, their routes were used by copy-cat bus services and eventually aided in the creation of motorways across the desert. Zvi Richter, a British Zionist with a vested interest in the colonial development of Palestine and the Middle East, remarked in a letter to his brother in 1943 that it was "a testament to the vision of the British imperial planners" that a journey that would originally take 30 days to complete had been reduced to approximately 20 hours.

But the routes did more than that: They made it easier for people to journey across four cities to visit family and friends, or simply explore. One Lebanese newspaper in 1924 wrote that the transport company had done more to unite Syria and Iraq than any politicians or ideology had been able to in a decade. And it was true: Many people were brought together on this route. Fuad Rayess, writing in Saudi Aramco World, recalled a conversation he had with another passenger on one of the last trips to Baghdad:

"'You know,’ he said, ‘I thought this trip was going to be very boring, but it has actually been, well, romantic.’ I stared at him in disbelief. Had he lost his senses? Was he teasing me? ‘I mean, look around,’ he said. ‘There's a little six-year-old girl who crooned to a doll in the middle of the desert so it would go to sleep. There's a teacher who thinks nothing of giving an English lesson at 40 miles an hour. There's a driver who used to be a Bedouin. One man is trying to get some valuable clothes through customs and a complete stranger is trying to show him how. And a Frenchman, off alone in Iraq without knowing a word of Arabic; an Iranian professor on his way back from Europe; a young girl mourning a brother who is somewhere at sea on the greatest adventure of his life; and a mother looking for a daughter who may be somewhere in Baghdad right now wondering if she'll ever see her again.’ He shook his head. ‘So many interesting people on one small bus.’"

Zouka Khanoum, an elderly resident of Beirut, echoed these words: "I never personally went… but my husband, may he rest in peace, had frequent trips to Baghdad. After every trip, he would come back with stories of those he’d met, and tell me about what wonderful and different people travelled by bus. He would say they were mostly ajaneb – foreigners – though."

Beyond all this, the bus route stoked the imaginations of all: Omar, a middle-aged man who grew up in Damascus towards the end of the Nairn era, recalls seeing the buses at their depot in Damascus. "As a child, I would grow so excited to see the buses, because in my mind, they represented this out-dated vision of what our countries could have been… I would see the buses frequently, but one day they just weren’t on the streets anymore."

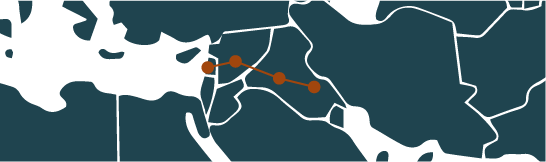

Watching the dissolution of borders and the formation of new ones in a region increasingly identified by its tragedies instead of its literature, architecture and beauty, it is hard to imagine that such a world was once possible, a world where anyone could take a bus from Haifa to Beirut, from Damascus to Baghdad. Remembering this, perhaps, can remind us that another world was within our reach not so very long ago.