While the van is driving underneath the Barbir intersection, a young woman seated on the first bench gives up her more comfortable seat to an older woman who has just entered the van. She instead sits on the narrow wooden plank that the driver has installed opposite the first row to accommodate extra passengers (and, of course, make more money - this is business after all). Suddenly the van, and all of us in it, swerves across the street, slows down and comes to a brief halt. Another passenger, a South Asian woman, enters and sits next to the young lady on the improvised wooden bench. While the younger and older women had exchanged a few polite words when they entered, this new woman says nothing and is not spoken to.

Behind her, I can see three men sitting in the driver's compartment. The driver seems a bit younger than the man sitting in the middle, who is definitely much older than the man sitting to his right. As I come to learn in my subsequent years of using this route, this is very unusual. The arrangement indicates that the younger man entered the van after the hajji seated in the middle, practically forcing a dignified man triple his age to move over to the left and slide - reluctantly, hesitantly, maybe even painfully - into the (very) uncomfortable middle seat. This is the narrowest spot in the van: wedged between the driver and the young man, cramped between the elevated seat and the ceiling, head bent down, the driver's gear-stick awkwardly positioned between his knees.

I slide the window open a little, and with my arm leaning on the cold metal window frame, I close my eyes and let the wind rush against my face. It's quiet in the van, and there isn't much noise outside either. I listen to the city float past, against the background of the driver's poor choice of cheesy holiday cheer. "Last Christmas I gave you my heart…"

I can hear the boys from the road-side cafés on the left yelling. Our driver slows down (but never really stops) as one of the boys runs inside, only to be back in no time with a fresh espresso. After paying the boy through his open window, the driver steps on the gas again. Up until this point, the route has traced the Green Line almost exactly, but this is perhaps one of its most infamous parts.

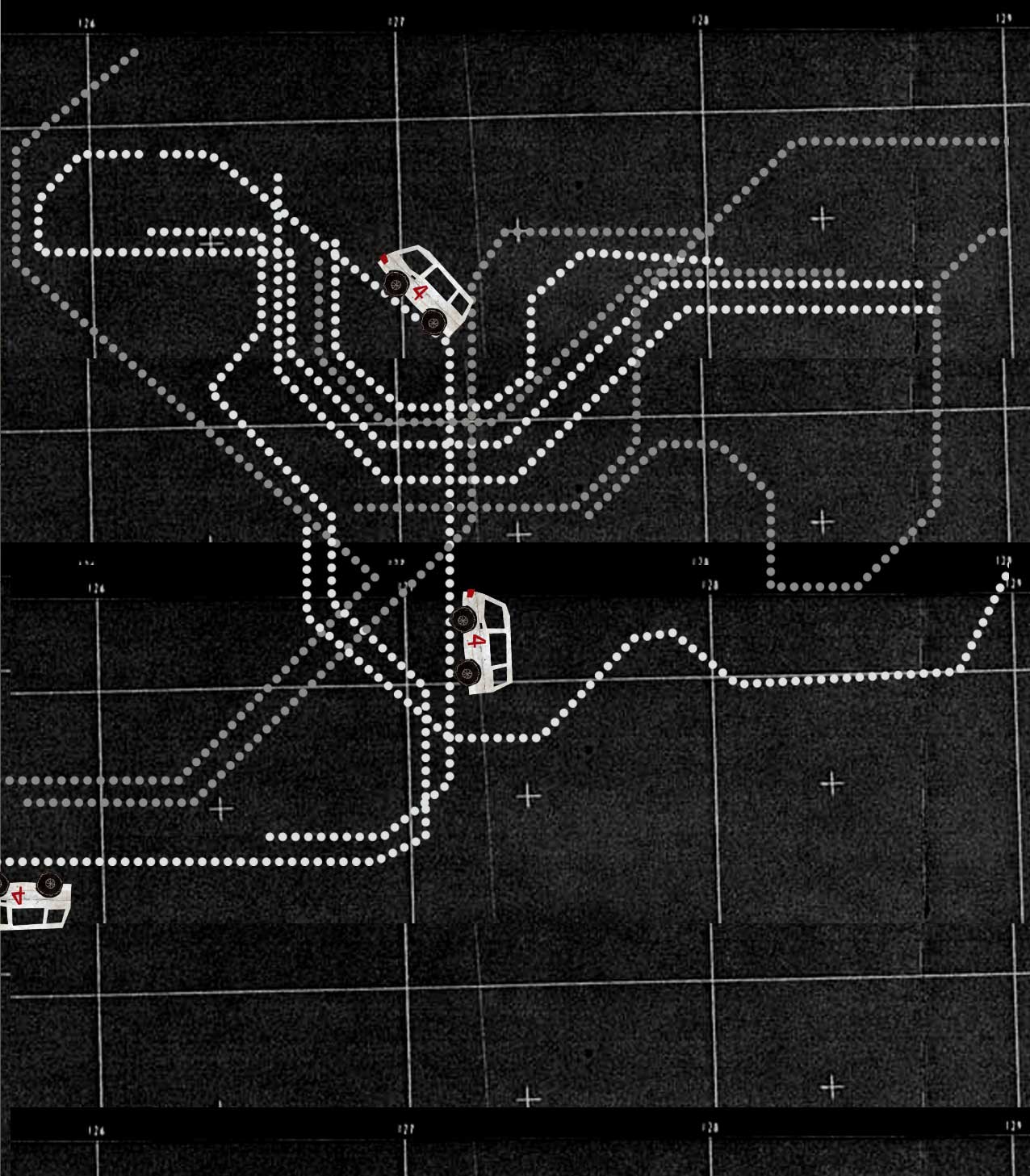

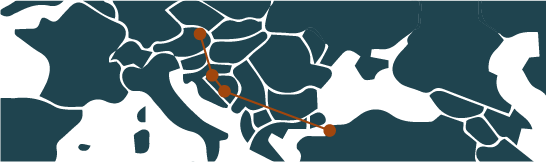

Bullet-ridden buildings frame us on both sides: left and right, "Shiite" Bachoura and "Christian" Monot. Driving along this part of the route, I often find myself wondering if the decades of violence perhaps somehow determined the routes these vans (and everybody else) takes through the city - I mean, they must have. Some friends of mine, for example, refuse to take the new highway towards the airport that runs through Beirut's southern suburbs, and instead choose an alternative route which takes considerably more time but runs through - what is for them - familiar territory. I can imagine that similar forces were at play in the historical formation of route No. 4. For now, however, this spot along the Green Line is just our driver's caffeine-stop.

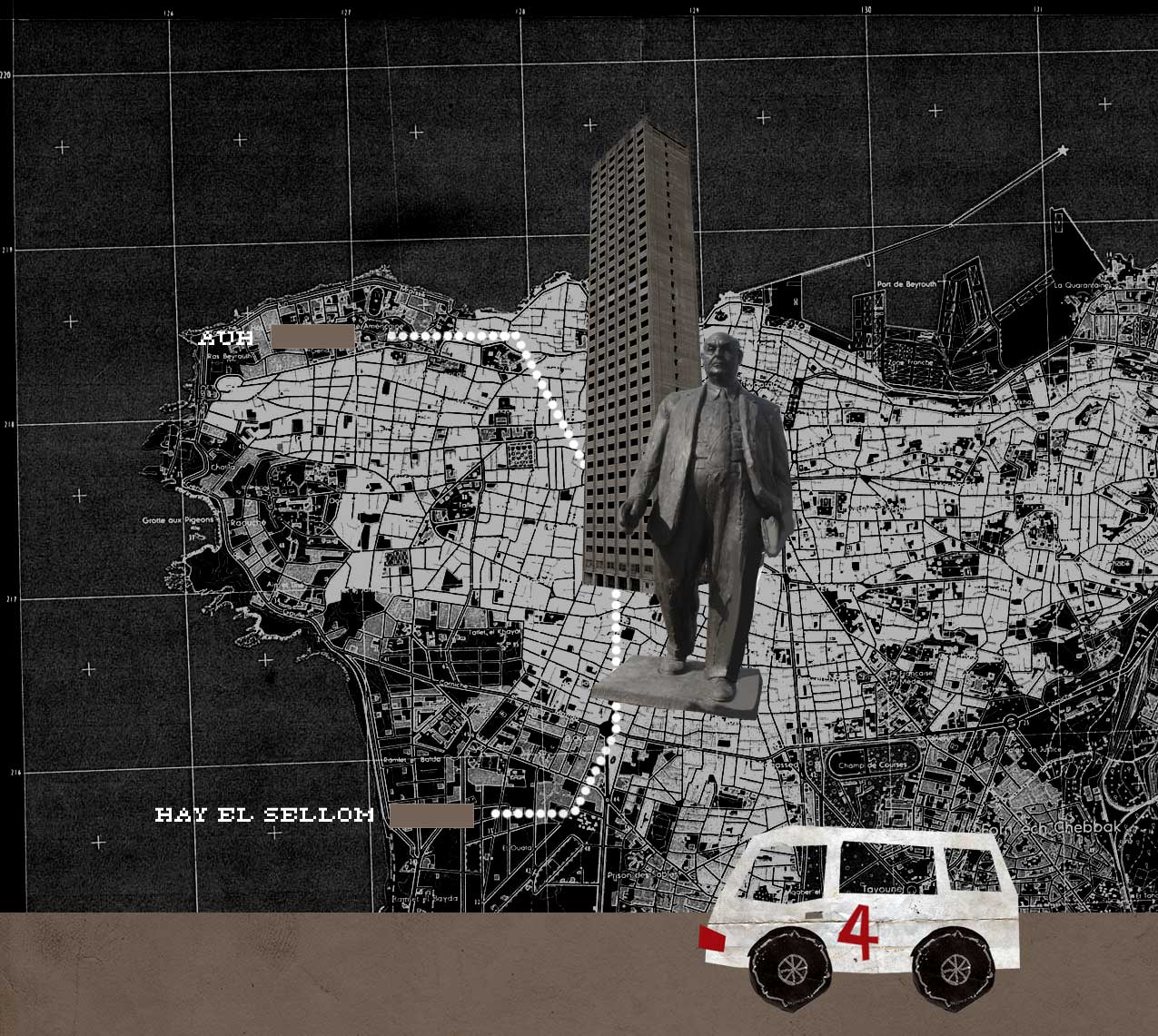

As we emerge from underneath the Ring Road into Downtown, I can feel the sun making its way through the clouds. I open my eyes again. We're driving towards Martyr's Square, with its backdrop of the majestic, blue-domed Mohammad al-Amin Mosque. This square has witnessed events of immense political and social significance for over a century - from the execution of Lebanese nationalists by the Ottomans during World War I to the massive demonstrations in 2005 that led to the departure of the Syrian army from Lebanese territory. Currently, however, it serves as a stage for some of the largest real-estate developments in the city, with construction sites springing up left and right. Thankfully, there is not a lot of traffic here today, and I'll only have to see the blur of cheap advertisements as we pass: "Every city needs its icon," and other such nonsense.

If you ask me, the real icon is actually standing solemnly across the street: the famous "Egg" theatre. Abandoned since the 1990's, it is an eyesore to many, and there have been plenty of projects aimed at either demolishing or redesigning it, none of which have been successful. For now, the Egg remains standing, unused but open to interpretation, summoning thoughts and memories of a time when things were different.

Ra'm arb'a is a thread, weaving together a fragile whole from a vast range of disparate places; places such as the Egg, Burj al-Murr, Horsh Beirut, the Green Line, Dahiyeh and Hamra. The route is an artery, connecting some of the city's most vital organs (not a few of which are struggling beneath the suffocating weight of local and regional pressures), and travelling along it regularly is a way to keep up with the city's pulse; to witness its changes in both their subtle and drastic forms. It is an experience of being "out in public," exposed to various others, and faced with the challenge of making some sort of sense out of the often incoherent chaos flowing by outside.

As we circle around the Egg to get onto the Ring, the van picks up speed again. The wind rushes in through the open window and I take a deep, slow breath. I'm glad to be on my way home.

We're almost there.