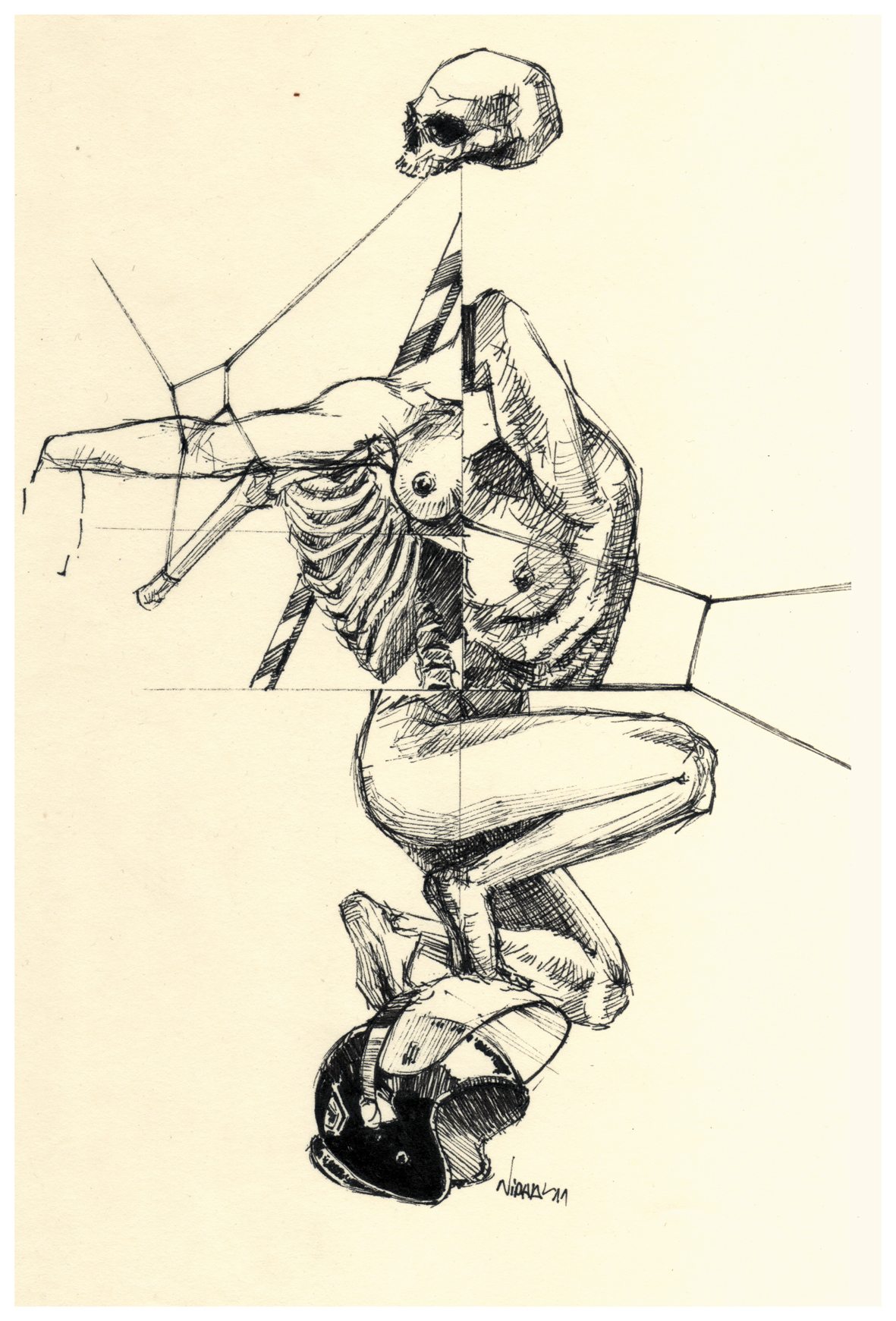

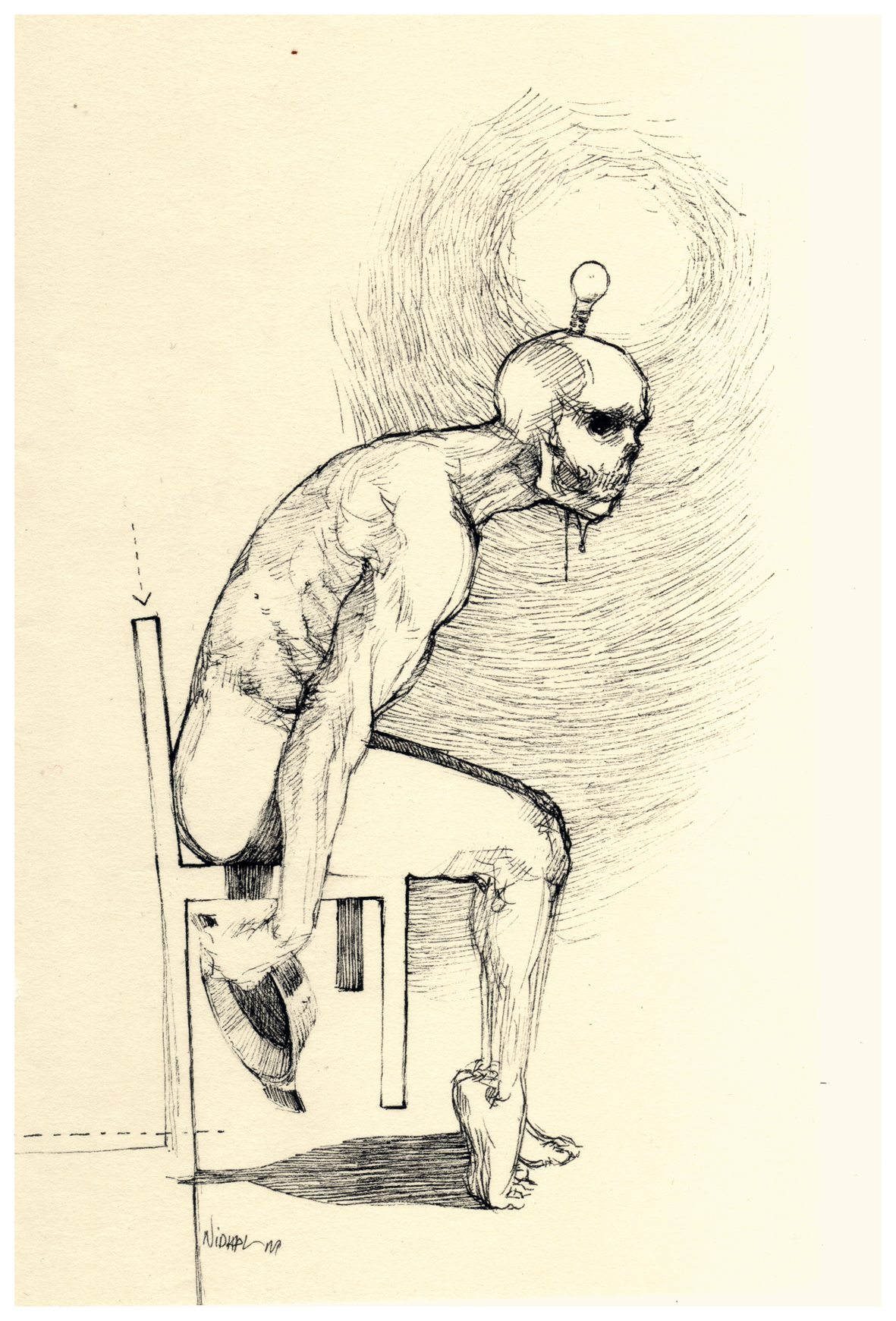

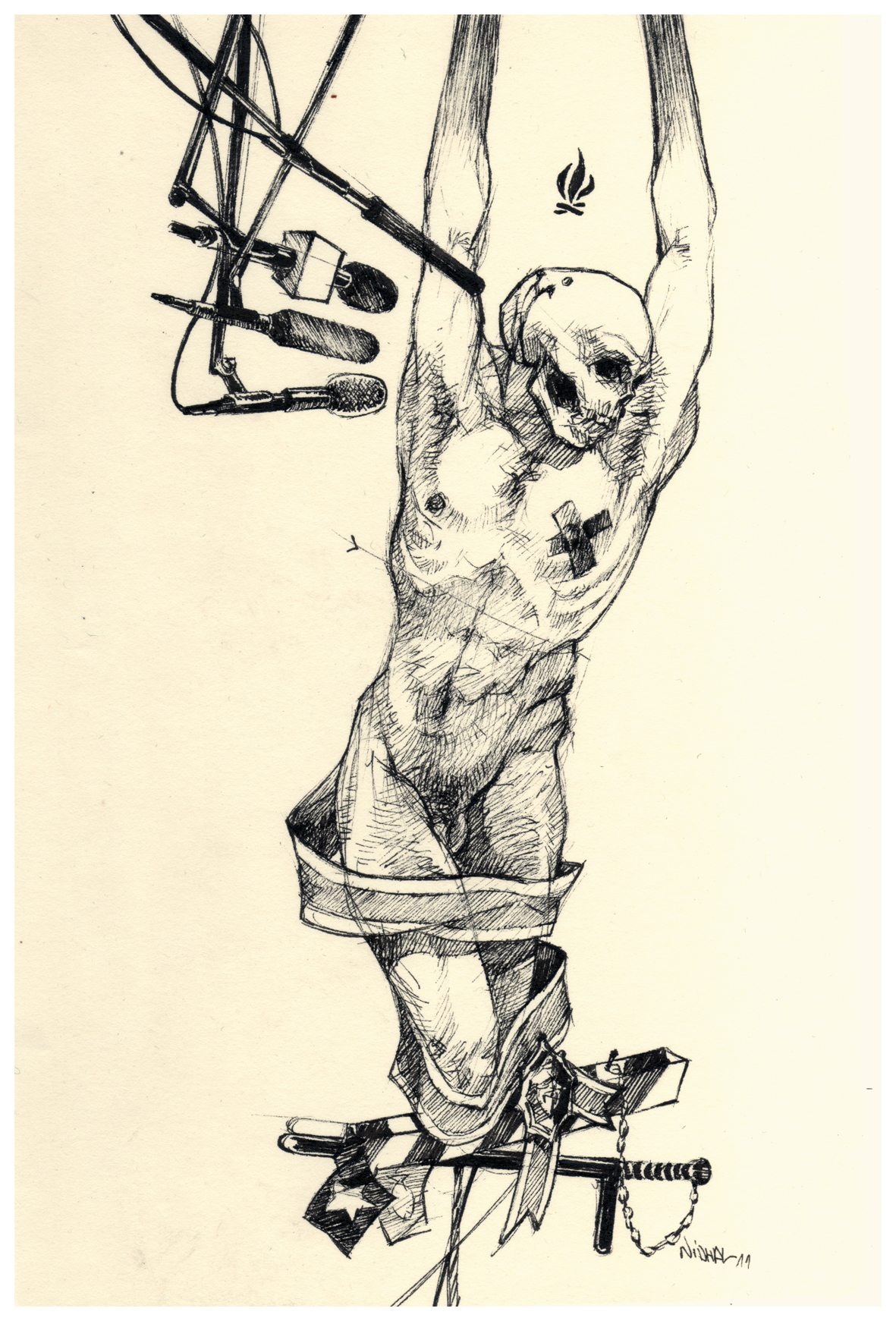

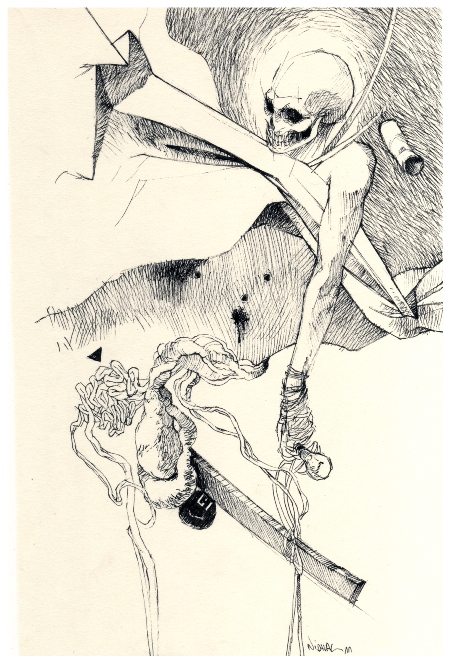

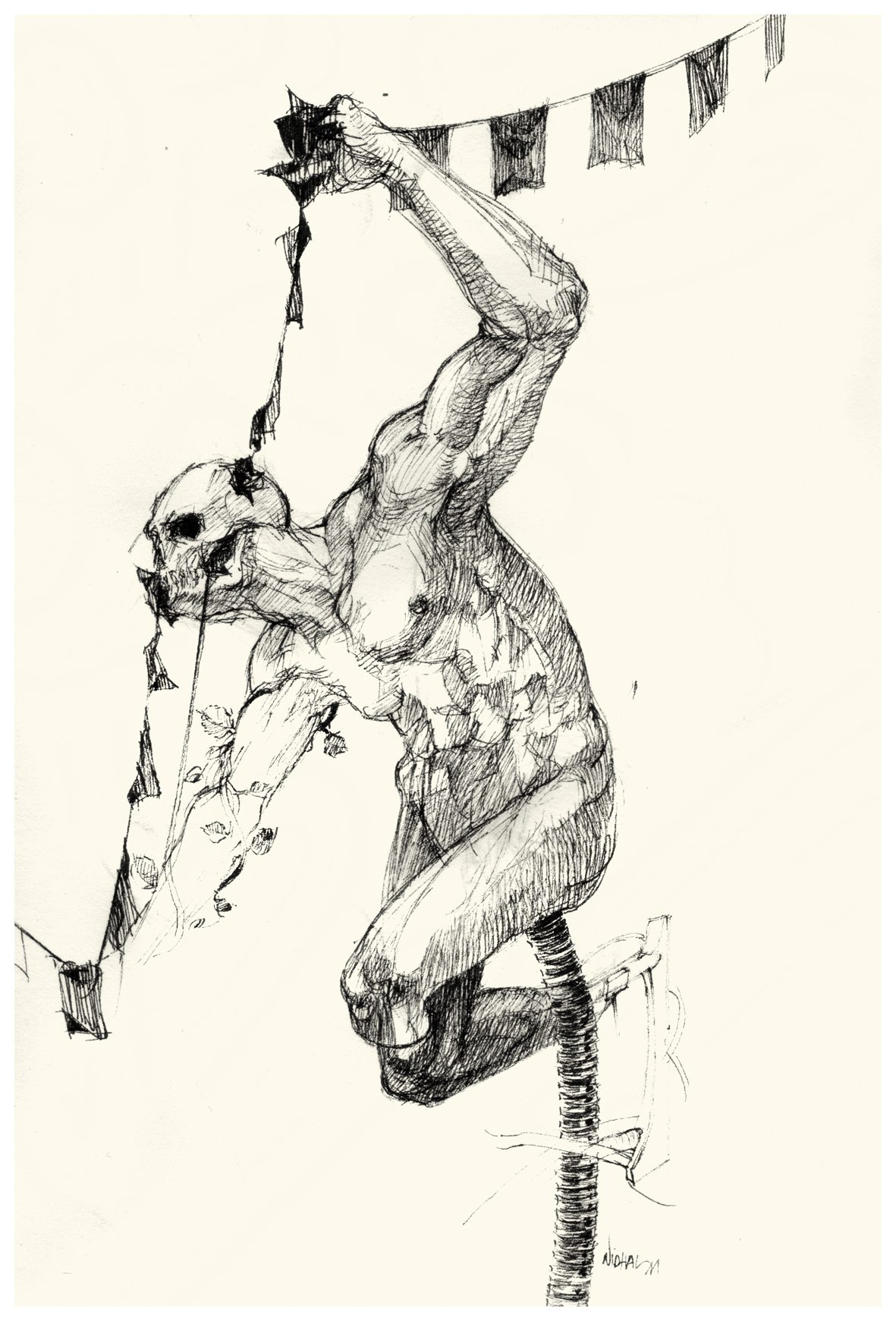

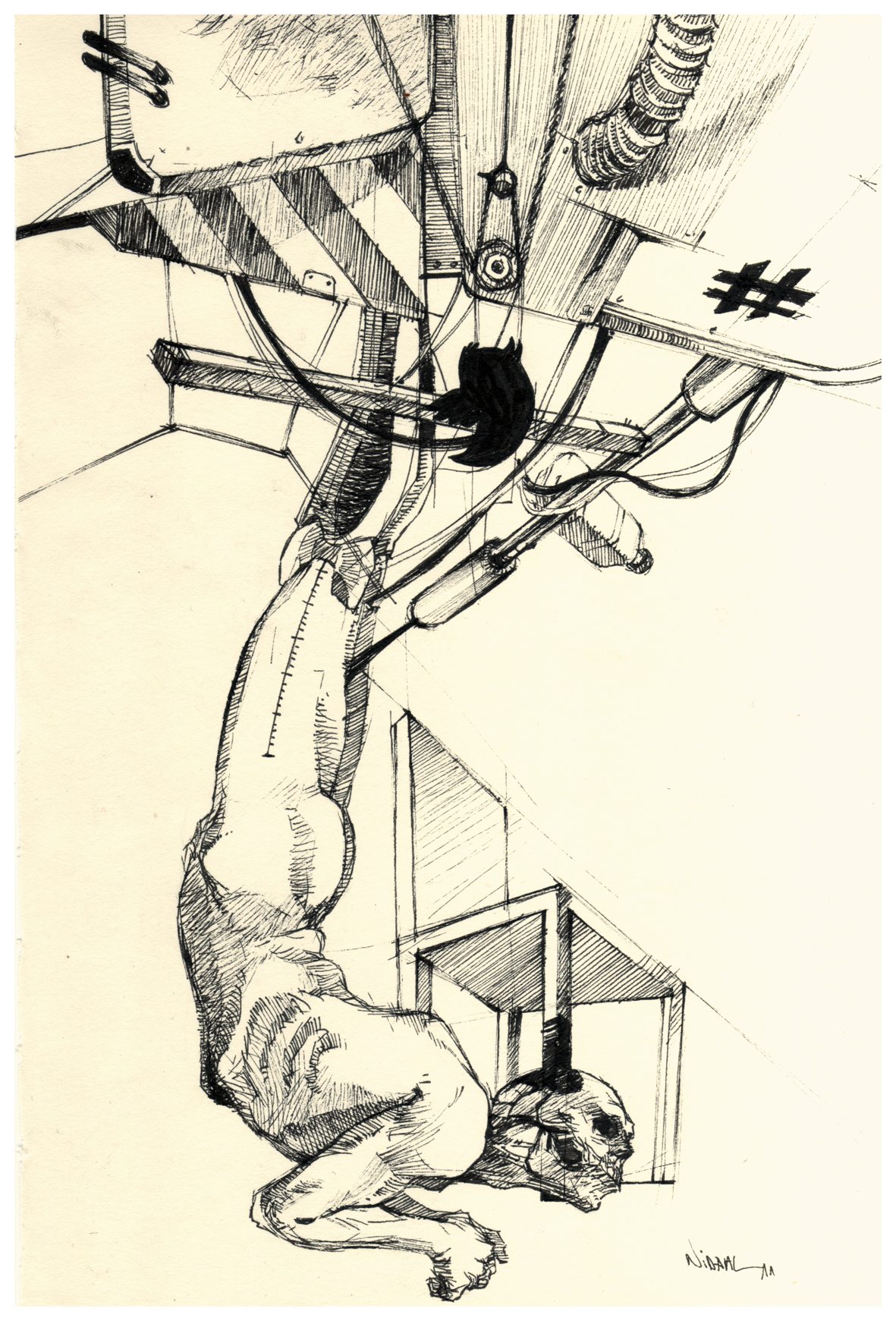

“A look at the Tunisian uprising – a look at a world that has lost its centre and tries, artificially, to put its pieces back together.” This is how Tunisian artist Nidhal Chamekh presents De quoi rêvent les martyrs ?, his recent project based on the writings of Tunisian philosopher and poet Slah Daoudi.

Nidhal, who lives in Paris where he’s pursuing doctoral research at the Sorbonne University, was born in the Tunisian town of Dahmani. Both his parents were activists and encouraged him at an early age to express himself through art; he exhibited for the first time at the age of 12. Last year, Nidhal started working on a series about the martyrs of the Tunisian revolution, to be exhibited at Beirut’s Art Factum Gallery between 30 January and 20 February, as part of a group exhibition called “Politics”. Mashallah had the opportunity to speak to Nidhal about his work.

Nidhal, who are you?

My name is Nidhal Chamekh. I was born in the town of Dahmani in western Tunisia, but I live and work in Paris. I’m mainly a painter and a drawer and currently a Ph.D. candidate in Plastic Arts at the Sorbonne.

How was your childhood? You grew up in an activist family, with both your parents involved in politics. How was that?

Both my father’s and mother’s families have been involved in struggles for independence since the French colonisation. Grandparents, aunts and uncles were all activists and syndicalists. So it was natural that my parents, too, took the road of social and political activism. My father was more radical; he chose to fight underground and was imprisoned several times under both Bourguiba’s and Ben Ali’s regimes. My mother chose to fight as a teacher in the syndicate. But both of them decided to not expose themselves in the media lights. That’s the impression that I have of them.

You mention that your parents were persecuted. As a child, how did you experience that?

Personally, I never really felt that I was in danger. Even during the more difficult and dramatic moments in our family, when my father was absent or in jail and the family was under surveillance, my mother always knew how to protect us. So, through her, I felt safe. What I remember most are the convictions against my father and our visits to him in jail.

Your artistic career started very early – you exhibited for the first time at the age of 12. How did it start?

My dad always made my artistic education a priority – maybe to make up for what he himself never had a chance to accomplish. So when I was a child, he always offered me objects and toys that he made himself, even when he was in jail. I think it all began with those handmade, pedagogical objects.

What about art? Is it a form of activism for you? Something that you inherited from your family?

Well, it depends on what meaning we give to the word “activism”. The kind of activism that is defined and formulated in a complete separation with the rest of life never interested me. Personally, I try to move beyond both the artistic and the political. I think that we should not be reduced to either and instead should draw from both of them at the same time. For me, the experience I have of activism is as a daily practice: a manner of living and a general form of resistance.

You currently live and work in Paris. But much of your recent work deals with Tunisia’s experience. Do you see Tunisia taking on a bigger role in your art since the move?

I’ve been in Paris since 2008 to finish my studies. Here, I’m able to scrutinise and examine pieces of art with my own eyes instead of seeing them in the scarce books that are available in Tunis. By the end of my studies at the School of Fine Arts in Tunis, I got a scholarship to study at the Sorbonne; without it, I would not have been able to cross the borders.

Actually, I don’t see how a country (as a homogenised entity) could influence my work. Tunisia is a cluster of cultural, sensational and memorial influences that I acquired by fate, from which I still draw in my work today and into which I also feed the rhythm of various encounters. I think the most important thing is the situation I’m experiencing being a foreigner. I’m not the first to say that the strangeness of the world can only be grasped by being a stranger.

Was your art immediately influenced by the revolution, or did that come later?

That came a year later. I had other things to do back then that were neither art nor politics. I think that art, even at its most effective, remains a mere promise. A utopian promise. But at that time, utopia was already there – it was flirting with the “actual.” Art and politics were overtaken by the present, by the current. There was neither art nor politics. Any previous forms of the two seemed obsolete. Since it [the revolution] started, Tunisians – both as individuals and as a people – have acted directly upon their present. They’ve changed themselves and their own lives and made their own stories become real.

Your series about martyrs is based on the writings of Slah Daoudi, a Tunisian who wrote poetry about the revolution right after it started. How has he influenced you?

I hadn’t read Slah Daoudi’s writings before the revolutionary movement, but I had met him. So I knew the person before getting to know his writings. He was among the anti-regime activists during Ben Ali’s era and during the 2011 events. What interested me about him were at least three inseparable things.

Firstly, I saw him at the beginning of the revolution when he walked the streets of Tunis (which by then had become agoras), distributing fragments of philosophical texts to passersby. Later on, I got to know him, as well as his conceptual rigour, more deeply. Secondly, his production is rather fragmented – it combines poetry, philosophy, political texts and translations. Finally, I find his writings interesting in their dealings with the idea of the martyr.

Edits by Angela Häkkilä and Stephanie Watt.