5/8

PORTUGUESE IN LEBANON:

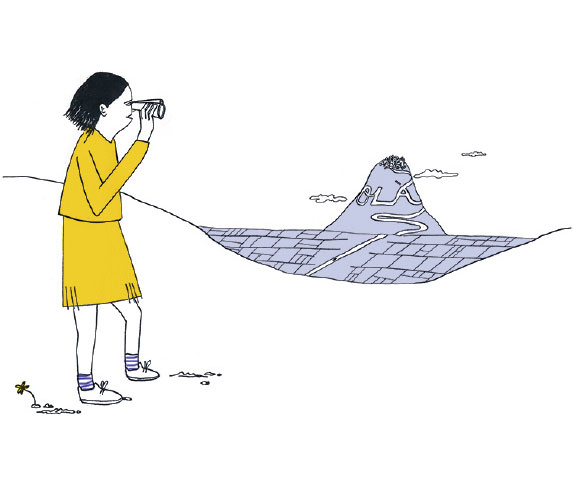

NEAR TO THE WILD HEART

by Gabriel Semerene

In Lebanon, the “Brazilian belt” is a group of neighbouring villages in West Bekaa where thousands of Lebanese-Brazilians live. Portuguese is part of daily life here, and is used for shop signs, family names and local small talk. For many families in the region, who have gone back and forth between Lebanon and Brazil for generations, Portuguese is part of being Lebanese.

Entering Ghazze, a village in the Lebanese West Beqaa district, the references to Brazil are numerous. The driver dropped me off by a sign reading “Brazil – travel agency ” in Arabic. The streets bordering the dusty road were deserted, as expected on a hot summer day in the middle of Ramadan. As I pushed the travel agency’s glass door, a young woman greeted me with a warm “Bem-vindo!” (Welcome in Portuguese) and a wide smile. Somehow her distinct São Paulo accent didn’t seem to fit the scenery.

Holud Smaili was born and raised in São Paulo, Brazil, to a Lebanese father from Ghazze and a Lebanese-Brazilian mother whose parents were also from this village. On her birth certificate her name is written as “Holud”, instead of the more common “Khouloud”, because her parents were afraid people in Brazil would call her “Koloodjee”, since the voiceless velar fricative consonant in Arabic transliterated as “kh” is nonexistent in Portuguese. However, they weren’t able to avoid the palatalisation of the soundless “d”, a phonetic feature typical to certain areas of Brazil. “People who weren’t of Arab descent would call me ‘Holoodjee,’” she reminisced, laughing.

Now 26 years old, Holud moved to Lebanon with her mother when she was 18. At first she wasn’t quite fond of the idea of starting anew in a country she had only visited once as a child, but finally gave in to her mother’s wishes. Despite the extreme contrast between São Paulo, an enormous and cosmopolitan metropolis, and Ghazze, population 6,150, the sizable Lebanese-Brazilian community in the area made her feel at home right away.

Ghazze lies in the “Brazilian belt,” together with the neighbouring villages of Lusi, Sultan Yacoub and Lala. Most families in the region have been going back and forth between Lebanon and Brazil for at least four generations. The area concentrates an important part of Lebanon’s 10,000 Brazilian citizens. Although there are no official numbers, a source from the Brazilian consulate in Beirut estimates that there are over 4,000 of their nationals in this part of the West Beqaa alone.

The result is that the use of Portuguese is widespread, especially in Lusi and Sultan Yacoub. “Even those who don’t have ties with Brazil pick up the language. I barely need to speak any Arabic in my daily life,” said Holud.

No sooner had she said that then a man came in carrying a small basket of fresh-picked strawberries. “Jibtillik morango!” (“I brought you strawberry [sic]”) said the man, mixing Arabic and Portuguese. Holud laughed soundly and thanked him. “See, everyone knows at least a few words,” she said, taking the basket from her friend.

“Have you ever had fresh strawberries from the Beqaa? You must have some!”, Holud exclaimed enthusiastically. I politely declined, out of solidarity with my fasting interviewee. “Nonsense! Don’t worry, I’m used to it,” she replied. “I’ve fasted in São Paulo for many years and people would always eat around me.”

As I delighted myself with the handful of strawberries Holud rinsed for me, I try to pursue my inquiry, asking her about her adaptation to life in Ghazze. She confided to me the hardships of being a Brazilian girl in a small town in Lebanon.

“We [Lebanese-Brazilians] usually don’t get along very well with the Lebanese. Especially if you’re a girl, they are wary of you. Other girls get jealous, and boys don’t take you seriously.” Holud speaks mainly Portuguese with her parents and siblings, but learned Arabic at an early age and was educated in an Islamic school in São Paulo. Still, her accent is easy to detect. “As soon as we open our mouths, people here can tell we are Brazilian.”

Most of her friends grew up in Brazil like her, settling in their parents’ or grandparents’ country once they reached adolescence. Holud cited security and education as the main reasons why parents insist their children move to Lebanon after a certain age, but also the fear their offspring will be influenced by Brazil’s “loose morals.”

Kazdoura in the Brazilian oasis

Born and raised in Santos – one of Brazil’s most important port cities, on the coast of the state of São Paulo – Ibrahim Smidi, 24, was sent to Lebanon by his parents when he was in his late teens. His parents are still in Santos and visit Lebanon every now and then. Even though he misses his friends at times, he seems to have become a completely different person since moving to Lebanon. “Every time I go back to Brazil and see my friends, I’m astonished by the things they say and do. I can’t believe I used to be like that when I used to live there.”

Unlike Holud, Ibrahim doesn’t live in Ghazze, but in Lusi. He offers to take me on a ride around the Brazilian oasis, as he calls it, into Lusi and Sultan Yacoub. “Quer que eu te leve pra fazer uma kazdoura?”, he proposed, starting the sentence in Portuguese with “do you want me to take you on” and ending with the Lebanese word for a ride, kazdoura.

Lusi, an exclusively residential area, boasts several luxurious mansions hinting at neoclassical architecture. The walls and fences surrounding the houses, in a place where they are utterly unnecessary, reminded me of the gated communities that abound in the suburbs of Brazilian cities, having become the rampart of the white upper-middle class. “Those were all built with Brazilian money,” said Ibrahim, listing the names of the families and the businesses they own with each house we passed. Explaining the differences between Lusi and Ghazze, he confessed his preference for the former. “Ghazze is just too mixed for me. There are many Brazilians, but also Venezuelans, Lebanese […] that’s too much. Here in Lusi, everyone is Brazilian.”

I was tempted to ask him if he didn’t think a Portuguese-speaking village in the middle of the Bekaa Valley wasn’t already quite a mixture, but it was clear that this population seemed, in Ibrahim’s eyes, a homogeneous one – as if the Lebanese part of the hyphenated identity had been annulled.

Besides the slightly different ethnic composition between Ghazze and the other villages of the Brazilian belt, there is an evident social class divide. Only a few decades ago, these villages were nothing more than forsaken townlets suffering from crippling poverty, occupying a marginal position even within the already peripheral and impoverished West Bekaa. This situation led local families to expatriate to the Americas, especially Brazil, but also Venezuela and the United States. The money they would send back to those who remained boosted the economy, attracting some newcomers who were not always welcomed. “People here are not very open […] If they see someone from outside the village, they find it suspicious,” explained Ibrahim.

Compared to Ghazze, the dwellers of Lusi and Sultan Yacoub are visibly better off. Besides the nouveau-riche houses and an opulent, fully equipped mosque, Lusi and Sultan Yacoub were endowed with generators and their own sanitation and water supply system. Ghazze still depends on the flawed state-provided water and electricity. The unequal distribution of wealth between locals and Lebanese-Brazilians suggests that it is not only the foreignness of the latter that constitutes them as a separate group, allowing the Portuguese language to endure. Speaking Portuguese is also a sign of status.

Simultaneously natives and foreigners, Lebanese-Brazilians, especially the younger ones, are confronted with the impossibility of total integration. They are, rather, participating in complex social dynamics in which language, nationality, social class and geography are intertwined.

At this point of my incursion into Bekaa’s Brazilian belt, the uniqueness of this Lusophone turf seemed indubitable. A separate sense of identity may explain why Lebanese-Brazilians in the region cling to Portuguese, but a major question remained unanswered: If hundreds of thousands emigrated from all regions of Lebanon to Brazil over the past 130 years, how come only this specific area developed a Portuguese-speaking community?

A tale of two languages

At the first glimpse, Portuguese and Arabic may seem to be linguistic antipodes. However, the presence of Portuguese in Lebanon could as well be seen as just another chapter in the long history connecting the Romance language with the Semitic one. It is worth remembering that the two languages go way back, having interacted on several occasions since the Umayyad conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in the early eighth century, before Portuguese was even Portuguese.

Indeed, the five centuries of Umayyad rule on what is now Portugal left a profound legacy on Old Portuguese. According to renowned Brazilian linguist Antônio Houaiss (incidentally a son of Lebanese immigrants), some 25 percent of Portuguese words stemmed from Arabic by the High Medieval Period. With the foundation of the Kingdom of Portugal in the 12th century, several efforts to “re-Latinise” the language, as well as the coining of Greek and Latin-based technical and scientific terms during the Renaissance, most of these Arabic words fell into oblivion. In modern times, the influence of other European languages, especially French, aggravated this trend, so much so that only a few of these words are normally used nowadays – azeite (olive oil, from Arabic al-zayt), alface (lettuce, from Arabic al-khass), aldeia (village, from Arabic al-day‘ah), to mention some examples.

A little more than a couple of centuries after the Umayyads were ousted, Portugal had become one of the first consolidated states in Europe and was building its own empire. Arabic and Portuguese met again on the shores of the Persian Gulf in the 16th century, when the Portuguese Empire controlled several trading posts in the Arabian Peninsula before they were chased away by the Persians.

History decided that the two languages would meet again in late 19th century Brazil, a former Portuguese colony. Since the end of the 19th century, hundreds of thousands of Lebanese people left their home country to Brazil, a migration flow that peaked between the 1920s and the 1940s, but never actually ceased entirely. If Lebanese, Syrians and other Arabs are now considered to be a successful, active group in Brazilian society, their integration process was a troubled one.

Language participated in the marginalisation of Arabic-speaking Levantines from Brazilian society. Immigrants were mocked for being unable to pronounce the consonants “p”,“v”, and “g”, as well as for their frequent grammatical mistakes. Cultural representations of Arabs in Brazil often depicted them as speaking incorrect Portuguese and mistaking the genders of words.

Arabic had a thriving life in Brazil during the first decades of the 20th century, Brazil becoming one of the main stages of the Mahjar literary movement. Writers such as Shafiq Maalouf, Nagib Constantine Haddad and Salwa Salama Atlas were important members of this movement, which initiated modern Arabic literature. There were also several Arabic-language newspapers, including Suriya al-Jadida (“New Syria”), run by Antoun Saadeh, founder of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party.

In the 1930s, new policies aimed at obliterating immigrant languages were implemented. Brazil had received millions of immigrants, mostly concentrated in the country’s south and southeast which is the most populous area of the country in general, and the survival of their languages was seen as a threat to the nation by influential far-right movements. Fearing stigmatisation, Arabic-speaking families shifted to Portuguese at home, leading subsequent generations to perceive Arabic as nothing but a reminiscence subsisting in a few words and phrases.

This migration movement was overwhelmingly composed of Christians, although Muslims, Jews and Druzes from Lebanon and Syria were all present as well. The scholar Gildas Brégain, taking the year of 1937 as a reference, stipulates that only 9 percent of Syrian and Lebanese emigrants to Brazil were Muslim. During the Lebanese civil war (1975-1990), Brazil received an important, though much smaller, flow of Lebanese immigrants. Among them, Muslims were more significantly represented, settling mainly in the state of São Paulo and in the city of Foz do Iguaçu, near the border with Paraguay and Argentina.

Currently, the Arabic language is much more preserved by the Muslim communities. The schools founded by Lebanese and Syrian Christians have all ceased to exist or become regular schools that no longer teach the language. On the other hand, Islamic schools teaching Arabic thrive in cities with a significant Muslim community, notably São Paulo, São Bernardo do Campo, Foz do Iguaçu and Curitiba.

Alô, Beirute

Far away from the Brazilian belt in the Bekaa, lusophone Beirut is discreet, and may perhaps even seem nonexistent to untrained eyes and ears. However, from Lebanese-Brazilians to Lebanese-Angolans, and from Portuguese expats to the Brazilian marines of UNIFIL’s Martime Task Force, what the Portuguese-speaking community in Beirut lacks in visibility, it compensates for with diversity.

Establishing itself as the institutional face of Portuguese in Beirut, the Centre Culturel Brésil-Liban (BrasiLiban) was founded in 2011. Its establishment fell within a period of expansion for Brazilian diplomatic activities and ambitions. Brazil has been making it clear it longs to become a more relevant actor in the Middle East, and its ties to Lebanon are paramount to rendering its interests in the region legitimate.

The popularity of Brazilian culture – or what is perceived as Brazilian culture abroad – provides the South American country with a source of soft power. Despite the existence of a few projects aimed at the Portuguese-speaking community, such as the Projeto Curumim (“Curumim project,” curumim being a word of Tupi origin meaning “child”), which helps Lebanese-Brazilian children living in Beirut preserving the language, it appears that the centre’s main goal is to enlarge Brazil’s cultural reach.

Offering Portuguese language classes, the centre currently hosts around 150 students. The reasons attracting people to learn Portuguese are more varied than Brazil’s image as a “cool” country. An important percentage of the students hold Brazilian citizenship, acquired through a member of the family who emigrated and then returned.

There are also those who see the language as an opportunity for doing business. Brazil’s expanding funding in research also draws graduate students and scholars willing to pursue their studies abroad, especially in the fields of medicine and plastic surgery. Due to military-cooperation agreements, BrasiLiban offers special classes for members of the Lebanese military forces. The centre recently started providing free Portuguese classes to Syrian refugees, perhaps to complement the Brazilian embassy’s refugee visa-application initiative.

Despite the Brazilian connection, Lebanon’s Portuguese-speaking community is not limited to those connected to Brazil. Another crossroads between the Portuguese language and Lebanese people is the African continent, where it is an official language in six countries. Although definitely less sizable and influential than the Lebanese diasporas in West African countries such as Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal or Nigeria, Lebanese communities exist in Guinea Bissau, Mozambique and Angola. The latter’s consistent economic growth has been attracting Lebanese traders for at least a decade, to the extent that the Lebanese foreign-affairs ministry declared in 2015 its intention to open an embassy in Angola and send a diplomatic mission to Mozambique. However, mirroring the current trends within the post-colonial Lusosphere, the Brazilian cultural centre concentrates everything Portuguese-related.

Beirut is also the seat of two Portuguese-language publications: the newspaper Gazeta de Beirute and the online magazine Connection Beirut. Both aim at building a bridge between Brazil and Lebanon, as well as bringing together Lebanon’s Portuguese-speaking community.

Is Portuguese a Lebanese language?

While exploring the diversity of Beirut’s Lusophony, I met with Naima Yazbek, a fourth-generation Lebanese-Brazilian who was drawn to her forefathers’ land thanks to her passion for baladi dance, better known in Western societies as belly dancing. Besides being a dancer, Naima also sings in a Brazilian music band called Xangô. Exchanging our impressions of Lebanese-Brazilian identity and the presence of Portuguese in Lebanon, I asked her if she would go as far as to say that Portuguese has become a Lebanese language.

“I think Portuguese is definitely a Lebanese language,” Naima answered. “ I wish people in Lebanon would acknowledge that there is a bigger Lebanon in Brazil than in Lebanon.” Naima’s sentiment suggests a transnational approach to Lebaneseness – can a country with such a huge and dispersed diaspora be limited to its own national borders? And if so many people who feel attached to Lebanese identity are native speakers of Portuguese, wouldn’t that make Portuguese a Lebanese language?

Such questions seemed quite transgressive to me, as a Lebanese-Brazilian who has always regretted the decline of Arabic in his family and within the Levantine community in Brazil, seeking to retrieve this missing link to my heritage. I had come to conceive Arabic as a Brazilian language, defending its preservation, and had seen many “Lebanese belts” in Brazil – but my brief immersion in lusophone Lebanon made me realise I had never really embraced Portuguese as a component of this network of affects and identities called Lebaneseness.

The existence of a large Lebanese-Brazilian community is widely known in Lebanon. Stating that there are “over 15 million Lebanese abroad, 8 million only in Brazil” has become part of the national narrative (although those figures are based on speculation, since the Brazilian census does not ask questions regarding ancestry – the actual numbers are most likely considerably lower).

However, Lebanese immigration to Brazil is more often thought of as a one-directional movement instead of a set of transnational and transcultural dynamics. Thousands of Lebanese who emigrated to Brazil returned to the Middle Eastern country at some point in their lives. Besides those who returned, there are also those who share their lives between both countries, creating a new, hybrid culture in which the Portuguese language plays an important role.

Therefore, Naima’s suggestion that Portuguese would be a Lebanese language disrupted a certain narrative on immigration and national identity. This idea also took me back to the Bekaa, more specifically to something Holud said when I asked if she intended to pass on the language to her children someday:

“I don’t think I could ever marry someone who only speaks Arabic […] and I will definitely raise my children in Portuguese. I mean, I really want them to speak good Arabic, too, but it would be weird to speak to them in Arabic […] Portuguese is the language of my heart.”

Beyond identity, status and social dynamics, languages play an important role within our affective registers. It is perhaps unimportant to ask whether Portuguese is a Lebanese language or if Arabic is sufficiently integrated into Brazil’s social fabric. To us, the offspring of this transcultural adventure, both languages will always be emotionally charged. As if they both had a special place – as writer Clarice Lispector said – near the wild heart.